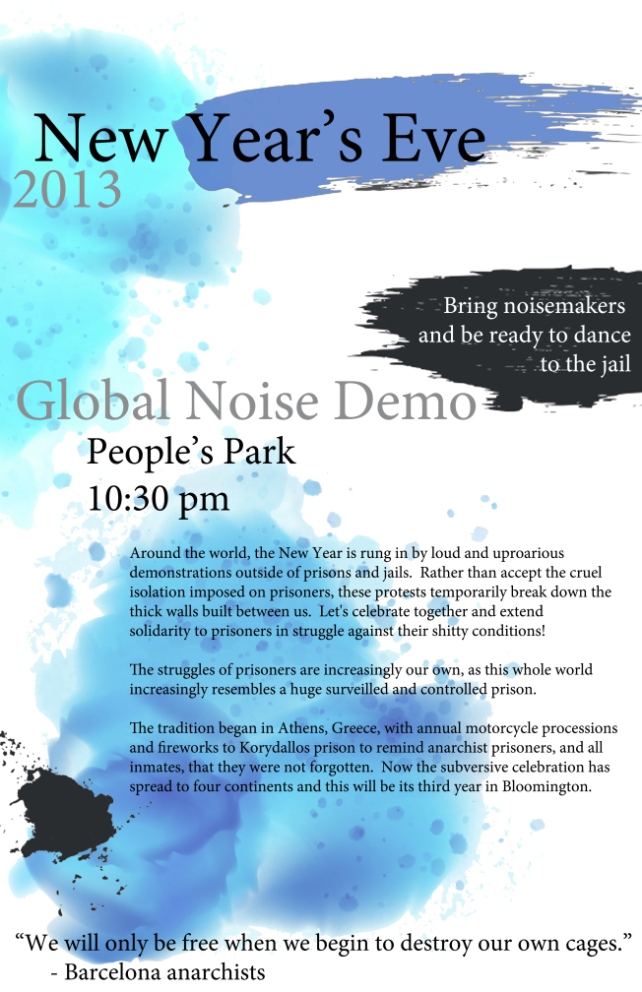

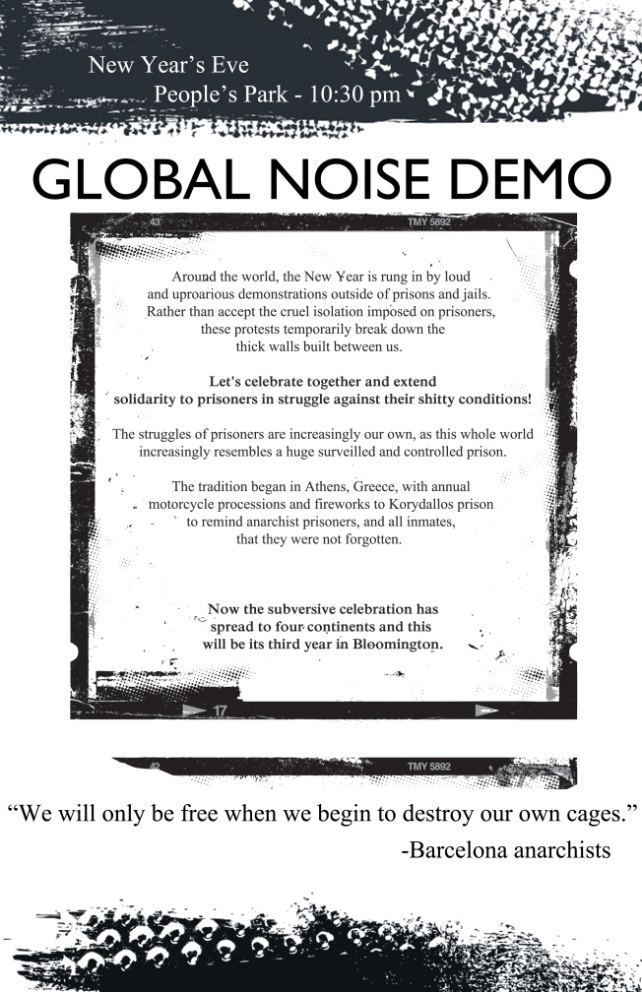

ABSENCE IN COMMON

Absence In Common: An Operator for an Inoperative Community

Click to access ia6_2_communitydomain_hamilton_absenceincommon.pdf

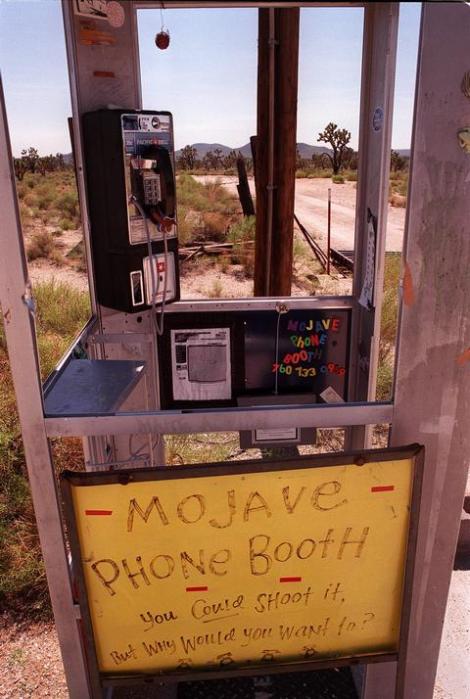

This essay by Kevin Hamilton is definitely one of the most profoundly affective pieces I’ve ever read. The circumstances and personal contexts of my life when I first came upon this essay were serendipitous to the vastness of its meaning. Its the vastness and void between people that Hamilton speaks about. Echoing Agamben’s desire for a “whatever singularity”, Hamilton takes us across Jean-Luc-Nancy’s threshold of “the singularity” and opens a contemplation of being by way of absence in common.

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/mojave-phone-booth

Claire Penticost

“Proposal for a New American Agriculture: Vermicomposted Cotton Flag

“Proposal for a New American Agriculture: Vermicomposted Cotton Flag

1. The center of the installation itself is the proposal of a new system of value based on living soil. To formalize this I have created a series “sculptural” objects from handmade soil, or compost. These represent units of a new currency, the soil-erg (provisional name), proposed as a replacement of the petro-dollar. In 1971, when U.S. President Richard Nixon ended trading of gold at a fixed price, formal links between the major world currencies and real commodities were severed. The gold standard was followed by a system of fiat currencies.

However, by 1973, Georgetown University economist Ibrahim Oweiss needed to coin the term “petrodollars” to describe the extraordinary significance of the circuit of capital running between a single commodity–crude oil–and a single currency–the U.S. dollar. While not formally fixed to international monetary values, the price of petroleum is the most determining value in the world economy. The dollar is an abstraction of value, the ultimate rendering of equivalence enabling all other commodities to be traded and circulated on a global market. Money as we know it has an obliterating function: it lets you forget all the human and nonhuman effort it takes to sustain life.

The important thing about the soil-erg is that it both is and is not an abstraction. Symbolically it refers to a field of value, but that value is of a special nature: it must be produced and maintained in a context. It is completely impractical to circulate it. It is heavy, and because of the loose structure required of good soil, it falls apart. It only makes sense when located in a place. The physical nature of the soil-erg both evokes and denies the possibility of coinage. If currency as we know it is the ultimate deterritorialization, the soil-erg is inherently territorialized. The forms of the objects themselves, large discs and stacks of ingots, reference the aesthetics of modernist serial abstraction. And yet just as the edifice of modernism is riddled with the cracks of unsustainability, they will eventually be subject to the entropic course of all organic matter.

From: http://www.publicamateur.org/

My first introduction to Claire Pentecost was in the zine Call To Farms, which can be found here:

“if you want environmental sustainability, work for social justice. As long as we segregate the risks and rewards of environmentally toxic industrialization, sustainability remains a specious marketing idea.”

A worthwhile interview can be found here: http://blog.art21.org/2012/01/31/5-questions-for-contemporary-practice-with-claire-pentecost/#.Ur8AQfvEqt8

“So much is needed, it’s a challenge to determine where to focus. The way to make a sustainable practice is to structure one’s contributions within the scope of one’s own needs and proclivities but with the aim of self-surpassing.”

And this exciting question, “Is the Bio- in BioArt the Bio- in Biopolitics?” is explored here:http://eipcp.net/transversal/0507/pentecost/en/base_edit

SHELTER

Flophouse

Occupants of flophouses generally share bathroom facilities and reside in very tight quarters. The people who make use of these places are often transients. Quarters in flophouses are typically very small, and may resemble office cubicles more than a regular room in a hotel or apartment building.

American flophouses date at least to the 19th century, but the term “flophouse” itself is only attested from 1904, originating in hobo slang. In the past, flophouses were sometimes called “lodging houses” or “workingmen’s hotels” and catered to hobos and transient workers such as seasonal railroad and agriculture workers, or migrant lumberjacks who would travel west during the summer to work and then return to an eastern or midwestern city such as Chicago to stay in a flophouse during the winter. This is described in the 1930 novel The Rambling Kid by Charles Ashleigh and the 1976 book The Human Cougar by Lloyd Morain. Another theme in Morain’s book is the gentrification which was then beginning and which has led cities to pressure flophouses to close.”

This house, with the “smoke weed” back-board, usually had an upside down cross (that the pentecostal neighbor would flip right-side up), usually had more trash in the yard piled high, dogs running loose, usually had more people hanging out there.

The lot to the right was being squatted, people who couldn’t afford the dump would dump truck-loads there and it would get burned to grill dumpstered meat or just to stay warm. People went there to drink, or sleep off a drunk. People went there to talk gibberish or shout at the voices in their heads, people went there to figure out if they had any other place to go. Or folks just stopped by to visit the neighbor.

This house is gone now. Five house on this block were torn down in three years. The first sign is a hole in the street from disconnecting the sewer-line. Days later, the noise of a back-hoe and dump truck. In three days, two workers raze, grade, and seed it with grass.

This house was different. It wasn’t empty, but neither were some of the others. Also, this didn’t just happen with two workers. There were three city agencies out to make sure this home was torn down. The resident was jailed during the process, and the neighbors stood out to watch.

Not too far from the tracks where hobos still jump in and out of town. Just up from the creek and where the shanty camp was demolished to pave the Greenway. This Google image is the image of a space claimed by dozens and dozens of people over the years, and a hand full of folks since childhood. The city “cleaned it up” and made a bigger mess of people’s lives.

Housing Our Selves

Housing is of special interest to me. I’ve built homes from the foundation up, in New Mexico, Colorado, Georgia, and Indiana. I’ve reclaimed a homestead in New Hampshire, bought a sliver of ground in Tallahassee for a yurt, and moved into a boxtruck. Starting in 2008, I and some friends bought three houses in downtown Evansville. The mortgage was split evenly by everyone who moved in ( mostly strangers ) and we shared common spaces. We considered ourselves to be living in “co-operative housing”. As time progressed the houses were put into a non-profit, Scnaubelt Sanctuary LLC, and managed by the residents, and then finally turned over to individual occupants.

In 2010 some of us from the co-op went to a lecture in New Harmony. The speaker was Charles Durrett, an author of Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves. I had read this book, as well as stayed at Sunward Cohousing in Ann Arbor when giving a presentation at a co-operative housing conference. So, the sterility was expected.

Sunward was advertising buy-ins at $350,000. per unit while we were there. The examples in Durrett’s book were a comparable exclusivity. When confronted by someone from our houses, during the Q&A, as to why we just sat through two hours of pictures of rich white people; Durrett responded, “If i had two more hours, I could show you so many pictures of people-of-color. I just don’t have the time.” In San Francisco and Vancouver, the average cost of a house is $600,000. so half that is quite a bargain. However, we live in Evansville. The purchase price for the three co-op houses was $70,000. The first house cost $45,000 (we paid too much), the second $18,000 (we paid too much), and the third $7,000. We housed over 40 people in three years, fifteen or so of those for multiple years.

The exclusivity in Durrett’s book and presentation wasn’t only financial, but too the design and placement for these “communities”, a word that could only be used in this circumstance hollowed out, to best fit the shallow and thin ties that Alain Badiou disdains between quotation marks to fit epithetic adjectives, “international communities”, the “human community”, “intentional communities”, etc.

One of the founders of the practice of Permaculture, Dave Holmgren, wrote in ( I think it was), Permaculture : Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, that intentional communities maybe incubators for innovation, but they fail to confront the basic permaculture principle of diversity, and instead tend to be homogenous. We should ask ourselves what is so novel about these forms of housing that distinguishes them from the neighborhoods in which we already live. How can we take advantage of the diversity (capitalist dispersal) of the people around us. One place I recommend to start looking for these answers is in the writing of Matt Hern, an anarchist and author who has written about successful interventions in opening and sharing spaces and resources in the existing community. http://www.mightymatthern.com/?page_id=156

Josiah Warren: “First American Anarchist”

Josiah Warren: “First American Anarchist”

Here is a link to the first biography of Josiah Warren, published in 1906. Warren has been considered the first American anarchist. He lived at New Harmony, In. for part of his life in the mid 1800s, as band director and philosopher. While in the area he opened an “equitable commerce” store, wherein the price for an item, avoiding profit, was set at a rate in equal exchange for the labor that produced it. Several other stores of this nature had been set up by Warren and received a sustainable success.

Joseph Heathcott: From Evansville to Practicle Anarchy

I was excited to first hear that an anarchist as active and prolific as Joseph Heathcott was from Evansville. Now a professor of Urban Studies at the New School in New York City, Heathcott has found time to encourage and prompt my inquiries. Here are two pieces that Joseph wrote; the first is a slice of life in Evansville, and the second is from an issue of the periodical Practical Anarchy that used to come out of the Midwest.

Remembering Evansville

Growing up in the rustbelt, the city was brown and haunted. I lived in a small house near a liquor store and a porn theater. Buses never came, factories never reopened, sad taverns loomed across from the parish church. Pebbly sidewalks cracked and crumbled. Small, rough front yards choked on tall grass, and mean dogs chained to clotheslines wore rutted dirt paths as they chased you, hoarse from barking. Cold mornings smelled like diesel. Weak Folger’s coffee and oatmeal fueled an Irish people. St. Christopher rode sentinel on the dashboard of dad’s Ford pickup with Merl Haggard over tinny AM radio. There was a bad house down the street that no kids would go near. Freight trains barreled down the middle of Main Street past the vinegar silos full of rotting fruit. That bully kept watch in front of the Dairy Queen; you had to sneak by to get home safely. Big Red soda rotted young teeth. Remember when the mayor was shot and killed by that crazy lady? All these things were there, all these things happened in the city.

FROM PRACTICAL ANARCHY:

Sustainability, to be sure, is a term so overused in discussions of food and natural resources that it is difficult to recover a core meaning. Third world development is now “sustainable.” Petrochemical exploration and extraction is now “sustainable.” Timber harvests are now “sustainable.” Perhaps human societies will never be able to maintain a purely and endlessly balanced relationship with the natural world; but clearly there are far better balances to be struck than our current system so radically out of whack that we in the developed North have lost nearly all conception of our daily bread as the staff of life. Indeed, we purchase highly processed, nearly unrecognizable food products, molded and packaged in a bewildering variety of shapes, colors, and sizes, retailed through mass corporate industrial supermarkets and fast food chains. We pop trays of “food product” into microwaves because we are so rushed and stressed by our workplaces and schools. Worst of all, we construct elaborate, calorie-obsessed diets that plunge us into sick, mechanical relationships with what we put into our bodies. Food becomes a calculated roster of nutrients, vitamins, minerals, proteins, fats, carbohydrates. Even vegetarian and vegan diets, steeped in narrow moral confines, threaten us with a loss of what is deeply and truly important in the way we eat.

The anarchist community has done a better job than most political groups in placing food close to our hearts, probably thanks to a strong infusion of environmental activists and social ecologists into the anarchist rank and file since the 1960s. Or, perhaps, anarchists just love to eat. At the same time, vegetarianism, veganism, and bioregionalism have made important inroads within the anarchist community, forcing us to confront our individual choices about food and to act with greater degrees of responsibility. In many ways, the intensely personal focus of these varied eating commitments made them especially ripe for absorption into anarchist politics a politics that, like feminism, recognizes that the personal is indeed political.

Yet the limitations of these diet choices have become increasingly evident, and mirror the limitations of anarchist politics more generally. While no one should denigrate people’s “lifestyle” choices, there is a real urgency to move forward with a synthetic political agenda that brings together personal choices with broader activist commitments. Merely being “vegan” is not enough. Not even close. In fact, strict and orthodox moral commitments to a particular diet may actually contravene responsible ecological food choices (using cane sugar as a sweeteners, for example, instead of locally produced honey; eating mass-produced and packaged egg-replacers produced 2000 miles away instead of a free-range egg gathered within shouting distance; refusing to eat a fish caught from a nearby stream while having no qualms about motoring through the Taco Bell “drive-thru” for corporate vegan burritos). Moral orthodoxy, whether in religious or dietary conviction, shuts down more studied and complex understandings of the world around us.

Practical Anarchy is a magazine devoted to heterodoxy rather than orthodoxy. Since this issue of Practical Anarchy is devoted to Food Politics, we will explore a range of critiques and alternatives to the current corporate capitalist food system. Our interest, as always, is to move beyond simplistic debates over “lifestylism,” to reject narrow confines and useless labels like “workerist” or “reformist,” to complicate narrow political choices about what we eat and how we come by it, and to bring a practical dimension to our political choices as an antidote to orthodoxy. We will look both at “negative” activism (activism pitched primarily against some component of the corporate capitalist food regime, which tends to be issue-oriented) and “positive” activism (activism which seeks to build alternative or parallel institutions). We see each of these activist approaches as important and mutually reenforcing.

Most of all, we at Practical Anarchy want to provoke more informed, nuanced, and pragmatic conversations about food and food politics, with the hopes of facilitating stronger activist projects dedicated to food issues. We want roadkill gourmands talking with vegan reichsters. We want environmentalists talking with labor activists. We want libertarian-leaning anarchists talking with social anarchists. Call us naive, say that we are Polyanna-ish, but we believe there is everything to be gained from supporting diverse approaches to food politics and food activism…and everything to lose by ignoring each other and miring ourselves in orthodoxy.

courthouse_t6072.jpg

BURN THEM ALL

In 1855 the Evansville courthouse burned to the ground on Christmas-eve. Why isn’t this a tradition?! In Athens Greece, people torch the giant Christmas tree in front of parliament every year, and then maybe riot. I’d be excited about Christmas, every year, if we could get back to this…

EVANSVILLE: HETEROTOPIA

EVANSVILLE: HETEROTOPIA Notes On Where We Are (and what I’m reading)

When I draw, I scribble.

I place trace paper over the scribble, and connect the lines that I like. The chaos becomes: people lounging, rolling hills, pools of water, houses, gardens, amphitheaters, barns, etc…

Urban planning can be understood much the same way. We can reorganize the lines of chaos. Drawing out what makes sense to us without a template. Using what we have, even if we can’t make sense of the whole, we can make something more meaningful of the few parts that we can grasp. Something about chaos is that it is not without order, but has infinite orders. “In 1900, in poorer districts of Paris, one toilet generally served 70 residents…Le Corbusier, for one, was horrified by such conditions. ‘ All cities have fallen into a state of anarchy,’ he remarked.” ( from The Architecture of Happiness- Alain de Botton) Here, Corbusier uses anarchy interchangeably with chaos. If we define anarchy for ourselves, instead of leaving it to professionals or history, we can redefine the city. We can set new limits. We can draw new lines. These are the lines Corbusier drew, sky scrapers to accommodate 40,000 people, and with lots of toilets.

When I lay trace paper over Corbusier’s drawing, I make something of a different scale. This could be in Corbusier’s Paris, a long walk from the towers, at the top of a hill in the park. A ramshackle silo, a community-hall spanning between tree tops, a collective house in the background with patio, a large pond in the foreground, a mishmash farm house with a black flag hanging from the awning. I could say that this is anarchy in the city, at the scale of companions, of manageable land, in a rift of the woods, with compostable toilets. Using the same materials, Le Corbusier’s lines, I can build what I want.

When we define a thing, be it a city, or anarchy, we set limits to it. We draw it’s edges, length, and size. We decide where it converges, and where it diverges. However, as long as our desire is a determining factor; the whole is dynamic, and the limits are open-ended. In The Owner Builder and the Code the Politics of Buiulding Your Home, co-author ( and self proclaimed “anarcho-decentralist”) Ken Kern remarks on the DIY building experience of psychiatrist Carl Jung: “Significantly, the building was many years in the making, and therefore symbolic of the slow, metered growth of his own consciousness. “ Jung said of his project, ” I built the house in sections always following the concrete needs of the moment…only afterwards did I see how all the parts fitted together and that a meaningful form had resulted…” The section is ended with this “ancient Chinese proverb, Man who finish house, is dead.”

Another author and builder who recognized the importance of impermanence to limits, was architect Cedric Price. Price held a demolitions license and advocated for raze of his constructions on more than one occasion. Believing, as Jung did, to “follow the concrete needs of the moment” might entail bulldozing the concrete that was needed in an earlier moment. Other projects of Price’s worked with open ended limits and impermanent lines. Price developed small structures that could be moved by people, about the city, and installed congruent to the flow of human movement. So, one of these small structures might be set against the entrance to a building, and seem to be the entrance, but when stepped into you might find a hot-tub, a video screen, a table set for tea, etc… and one could step right through on their way, into the building, and so it did act as an entrance. The structure could be set many places, in the middle of sidewalks, wedged between buildings, in empty fields or parking lots, etc… One of his more famous projects was a building with a crane built-in over head, and all the rooms built as self supporting structures, so you could use the crane to move rooms around, stacking them, lining them up, opening up the middle to create a large center room, etc…

Price was determined to build an environment which the purpose of was to be effected by those using it.

The Fun Palace, by Cedric Price, “…dialogue might be the only excuse for architecture.”

A strong point to get down is that we do effect our environments, and they affect us. In Desmond Morris’ book, The Human Zoo, he expands on the civilized trend toward confinement, and the self-destructive behaviors people use to cope. In one section he describes dominating those confined with you, as a way people cope, and says, “It is not enough to have power, one must be observed to have power.” You have to demonstrate your power; your potential to impact your environment must be exhibited. This dynamic might be the crux of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle. Systemic or institutional power often has enormous buildings as obvious monoliths of their power. Colin Ward, in a collection of essays titled, Vandalism, picks up on the smaller signs of power. A broken window can convey that random people have power, and a boarded up window can mean that the people in the monoliths have more control of that power. Morris suggests that this example of Ward’s is significant, in that the board is reactive, and those in control are telling that they are not in total control. It becomes a skill to read the landscape and understand where the seams are tearing, where time has eaten holes, where the cinders will catch, and which strands will fray beyond

the edges. What we might be trying to foster, is a craft, much like cartography. Make a map of where the population is already acting outside the intended use of an area, where crime is congruent to the flow of human movement, where rattling the bars of the cage has shook them loose, where people have exhibited the will and desire to move lines. These points are acutely drawn in URBAN PLANNING AND REVOLT: A SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF THE DECEMBER 2008 UPRISING IN ATHENS, “Urban space operates as a symbol of power and authority, as a signal of overall dominance in political and everyday life… And if the dominant is the person who has the capacity to change the rules (the capacity to install an exception) then the revolted were dominant over the production of their space: they were producers of a rupture in the everyday life of the city.”

In the zine Anarchist Urban Planning & Place Theory, its author, Olympia Teveter, deducts “…that if Geography is the study of ‘place’ and if what they (geographers) study are the unique differentiations at a location and how that location relates to other locations, then geography is in a very rudimentary way the study of environmental differentiations, and a ‘place’ is a perception of unique differentiation in a physical location. That is how you know that you are in a specific place, because you sense its defining, unique characteristics, whether those perceptions are physical or something else.” The unique differentiation in this physical location (Evansville) is our agency, our realizing of the potential to affect our location. Evansville is the space in which our resonance( like string-theory) shapes a geography, where our bodies determine ecology, where our hands leave prints, and our conspiracies take place. We define Evansville. Teveter says, “From my examination of planning and design theory literature at present, almost all of the literature appears to revolve around the nature of ownership…The structure of owner/non-owner is everywhere. “ Most maps of Evansville, use a geography that differentiates what is owned and who owns it, and not who uses it, and how they use it. We want a map of what we can grasp.

In The Future of Vandalism, Colin Ward, quotes N.J. Habraken , drawing the distinction between ownership (or property) and possession, “ We may possess something which is not our property, and conversely something may be our property which we do not possess. Property is a legal term, but the idea of possession is inextricably connected with action. To possess something we have to take possession. Something becomes our possession because it shows traces of our existence…” Habraken goes on to tell what might be done with the “structure of ownership”, “The question is not whether we have to adjust with difficulty to what has been produced with even more difficulty, but whether we make something which from the beginning is totally part of ourselves, for better or worse. The only way in which the population can make its impression on the immense armada which has gotten stranded around our city center is to wear them out. Destruction is the only way left. “ To attempt to take possession of the place we live is to go to war. It has been this way for centuries. The “unique differentiation” of the place of war, is often destruction. The mapping of the state’s offensive is the official destruction, demolitions, neglect, rezoning, highways, commercialism, etc…The mapping of the insurgency is vandalism, necessity, communalism, neglect, the transgression of lines, the breaking of limits, trespassing, etc…

This discussion of difficulty, is brought forward in War and Architecture, by Lebbeus Woods. “The flow of information between people on a communal scale bears a conceptual resemblance to the remnants of war in the old city: it is rational in its intentions, but unpredictable in its effects. …Architecture must learn to transform the violence, even as violence knows how to transform the architecture. …In the spaces voided by destruction, new structures are injected… difficult to occupy, freespaces are, at their inception, useless and meaningless spaces. They become useful and acquire meaning only as they are inhabited by particular people. Traditional links with centralized authority, with deterministic and coercive systems, are disrupted. People assume the benefits and burdens of self-organization…The new spaces of habitation constructed on the existential remnants of war…build upon the shattered form of the old order a new category of order inherent only in present conditions…There is an ethical and moral commitment in such an existence, and therefore a bases for community. “

Lebious Woods’ Scar Construction, “Acceptance of the scar… by articulating differences…divides and joins together… mandates a society founded on differences, not similarities between people and things. The city of self-responsible people… exhibits its unique scars…”

Useless and meaningless spaces; this is what Woods recommends we build. Spaces with no purpose, but to be given purpose by those so inclined to use them. However, Woods understands that this inclination is not one of whimsy, but one of being at war. This giving of purpose is the meeting place of Nihilism and Existentialism. In Ethics of Ambiguity, Simone Beauvoir describes the nihilist as negating meaning, and the existentialist as choosing the void of negation as the space to place meaning. In a way, capitalism makes the project of the nihilist simple. As asserted in Nihilist Communism, capitalism organizes us.

Capitalism reduces, but does not negate, all things to an economic derivative. The capitalist urban planner has, intentionally or not, been busy with the rational project of the reproduction of sameness, a war of leveling. This redundancy allows for the ease of killing all birds with one stone. It has made space for the realization that “All things are possible” Shestove, “All things are permissible” Os Cangaceiros, and “All’s fair in love and war” et al. The project of the nihilist urban dweller is to negate the meaning of spaces, and make them meaningless. Capitalism’s project is similar, is the project of simulation.

“At the dawn of Industrialism, factories were modeled after prisons. In its twilight, prisons are now modeled after factories.” -Os Cangaceiros …

The existential urban dweller doesn’t fill this void, but uses it for the unpredictable,” in spaces within spaces.” Giorgio Agamben says of “an absolutely unrepresentable community”, that it is located in an “unrepresentable space”, which the proper name of is Ease. “The term ‘ease’ in fact designates, according to its etymology, the space adjacent, the empty place where each can move freely, in a semantic constellation where special proximity borders on opportune time and convenience borders on the correct relation.” They say that this use is “the most difficult task”. Here, isn’t a design for utopia. Here we are, in hell.

But, this “coming community”, is existing in-between, in a purgatory, in the possibility of hell or heaven. In Richard Sennett’s book, Uses of Disorder, they write, “… people have learned in their individual lives, the very tools of avoiding pain later to be shared together in a repressive, coherent, community myth…the myth of a common ‘us’ is an act of repression, not simply because it excludes outsiders or deviants from a particular community, but because of what it requires of those who are the elect, the included ones. …this inability to deal with disorder …is inevitable when people shape their common lives so that their only sense of relatedness is the sense in which they feel themselves to be the same. It is because people are uneasy and intolerant with ambiguity and discord in their own lives that they do not know how to deal with painful disorder in a social setting…“ We choose to use the myth of hell, to burn away the memories of a communal history that never happened. The existentialist notes that the design of hell has no exits, only cells for confined security; our project is to “suffer the intrusion of others by necessity.” We cannot blow-up a social relation, but social relations can be explosive. This existential project is to learn how to live in hell, always on fire, making the best of the worst of people. War is difficult, and a way of suffering; the spaces we build must allow for this, as well as freedom. Such a place is Hell.

Hell, with the sinners, criminals, unrepentant, damned, forsaken, and free. Growing up, two of the locations given for Hell were one: the center of the earth, beneath our feet, sloshing back and forth never hitting bottom as the world rotates; and two: in an eternal memory of our lives, reliving every imperfect moment, forever responsible for our mistakes. In both cases, Hell is terrestrial. “In both cases the spectacle is nothing more than an image of happy unification surrounded by desolation and fear at the tranquil center of misery. “ Hell, because in the dichotomy of either or, as well as the in-between either or of the purgatory, we choose hell because we do not choose the bliss of oblivion, the passivity of the object waiting to be acted upon or chosen. We are not the elect, we do not watch for the elected. Hell, because we choose though we are unqualified to choose. Hell, because poverty is miserable, space is alienating, boredom is torment, and survival is hopeless.

Evansville is hell, where we are allowed to do whatever we want, and we will suffer our own affectivity. Ursula K. Le Guinn said of anarchism, “ It is choosing to be responsible for the choices you make.” Our anarchism, our Evansville, is hell; because Heaven is given to us, made for us, purged, purified, and prepared, but we choose hell.

Historic nihilists, in Russia, were educated youth, who chose to live among the peasant villages because there they believed life was closer to its origins, capable of subsistence, and desperate for revolution. When this revolution failed to materialize, they turned to the destruction of the world it was to replace. Today we nihilists might try again. Capitalism has eaten to decay the matter of life for its poor. America has become for many people here, a purgatory, a place of opportunity, a place of potential to reach heaven or be damned to hell. My suggestion is that we choose hell. A heaven here only damns the others to hell. Hell here, displaces heaven and allows for it to be located anywhere. Anywhere Evansville, a home for nihilists, a place built on a space of suspended disbelief. From beneath, behind, about, adjacent, and entangled to a non-local parallel, to “necessities of the particular”…Evansville is empty to such a degree that absence and alienation are the relation most in common. And though for most, a city is defined by the density within geographic limits…we choose a density of interactions, a density of meaning. Hell “exists in a concentrated or diffuse form depending on the necessities of the particular stage of misery which it denies and supports… different forms of the same alienation confront each other, all of them built on real contradictions which are repressed.” We will be unrepressed, unelected, we will unleash the beast and open the gate to hell, not acting out revolution on the stage of misery, but revolting against misery itself we’ll tear apart the stage and decimate the theater of war.

The architecture of this hell is built from a blueprint on the underside of Borges’ map, which hides the natural landscape, and so gives to us a secret world beneath it, ” a unity of misery”. The Art Of Darkness: Deception and Urban Operations depicts this secrecy, in a classic image of hell as a labyrinth. A large city provides several planes of urban high ground, and in many instances a subterranean level in addition … mobility is a great strength. Using back alleys and sewers, slipping through basements…buildings provide cover and concealment; limit or increase fields of observation and fire; and canalize, restrict, or block movement of forces, especially mechanized forces.

Again, Capitalism has already instituted this deception. “Deception is information designed to manipulate the behavior of others by inducing them to accept a false or distorted presentation of their environment- physical, social, or political.”(Whaley) Capitalism’s mode of alienation has displaced people from their environment, both in removing them from a stable location, as well as rendering them incapable of mentally establishing their bearings. People tend to subjectively picture the place they live, eliminating buildings and throughways. This was intentionally used by the KGB in the USSR, where their own maps excluded buildings and areas that the government didn’t want outside forces to be aware of, so upon invasion, enemy forces would be lost in the reality they’d find. (Urban Guerrilla Warfare- Anthony James Joes) This can be used to the advantage of the urban insurrectionist, because the places of “ease”, and the secret passage ways already exist, we already use them to move between the spectacle of the reified world, like dark-matter surrounding the visible universe. We just have to use them now for attack. Miserable, depressed, alone, and tortured, but in solidarity: from hell, solidarity means ATTACK!

TOTAL RESISTANCE : Swiss Army Guide To Guerrilla Warfare And Underground Operations, forwarded by a retired Coronal from the US army. It’s a manual for Swiss citizenry on how to insurrect if occupied by an outside force. In the section General Uprising, it says, “ Procure a lot of city maps for your selves… lease apartments, shops or even houses where you can take up position long beforehand, i.e., at bridges, intersections, train stations, telephone offices, exit routs, etc…

This panel, titled “Security of an Underground Meeting”, makes these suggestions, “reports are made over civilian phones using code words. Pose as newspaper reader-appearance of police vehicles will be reported; pose as a person resting in a park-surveillance of police barracks must be reported; and pose as lovers-approaching of squad car reported…” We don’t need to pose, we are already actually reading, loving, sitting in parks, etc… We have to be vigilant that we’re doing it while at war, that we’re being watched because our regular lives are in conflict with our enemies’ regulations. Life in hell is life at war, and we’ll be damned to hell one way or the other, the point is to choose it. Death comes to us no matter whether we take a position against it or not, but as the bank robber and escapee, Mesrine, said, “No one kills me until I say so.” We can choose to die fighting a war where we take ground, live in a place devastated by our intentions, burn ourselves out hotter than any blue flame of hell’s misery. Life is suffering; I suggest we suffer in love, in passion, and in rage: it will look something like this life looks, because it is this life, because again my point is that we are at war, we have been this whole time, and we will be.

As Colin Ward wrote, “The future will be just like this, only more so.” Let us be more. A density of diffuse commonality, a sudden conclusion of a question, a big bang, a natural phenomenon, normal people uncontrolled, builders of our own architecture we dismantle our own philosophy by constructing our own incomprehensible biology, tear down the fences, get lost in the commons. When we can control our own bodies, it will be far less important for us to control the world around us. But now, we desperately desire private places to do with our bodies what we like. To find those places we must do with the world around us what we like.