Josiah Warren: “First American Anarchist”

Josiah Warren: “First American Anarchist”

Here is a link to the first biography of Josiah Warren, published in 1906. Warren has been considered the first American anarchist. He lived at New Harmony, In. for part of his life in the mid 1800s, as band director and philosopher. While in the area he opened an “equitable commerce” store, wherein the price for an item, avoiding profit, was set at a rate in equal exchange for the labor that produced it. Several other stores of this nature had been set up by Warren and received a sustainable success.

Joseph Heathcott: From Evansville to Practicle Anarchy

I was excited to first hear that an anarchist as active and prolific as Joseph Heathcott was from Evansville. Now a professor of Urban Studies at the New School in New York City, Heathcott has found time to encourage and prompt my inquiries. Here are two pieces that Joseph wrote; the first is a slice of life in Evansville, and the second is from an issue of the periodical Practical Anarchy that used to come out of the Midwest.

Remembering Evansville

Growing up in the rustbelt, the city was brown and haunted. I lived in a small house near a liquor store and a porn theater. Buses never came, factories never reopened, sad taverns loomed across from the parish church. Pebbly sidewalks cracked and crumbled. Small, rough front yards choked on tall grass, and mean dogs chained to clotheslines wore rutted dirt paths as they chased you, hoarse from barking. Cold mornings smelled like diesel. Weak Folger’s coffee and oatmeal fueled an Irish people. St. Christopher rode sentinel on the dashboard of dad’s Ford pickup with Merl Haggard over tinny AM radio. There was a bad house down the street that no kids would go near. Freight trains barreled down the middle of Main Street past the vinegar silos full of rotting fruit. That bully kept watch in front of the Dairy Queen; you had to sneak by to get home safely. Big Red soda rotted young teeth. Remember when the mayor was shot and killed by that crazy lady? All these things were there, all these things happened in the city.

FROM PRACTICAL ANARCHY:

Sustainability, to be sure, is a term so overused in discussions of food and natural resources that it is difficult to recover a core meaning. Third world development is now “sustainable.” Petrochemical exploration and extraction is now “sustainable.” Timber harvests are now “sustainable.” Perhaps human societies will never be able to maintain a purely and endlessly balanced relationship with the natural world; but clearly there are far better balances to be struck than our current system so radically out of whack that we in the developed North have lost nearly all conception of our daily bread as the staff of life. Indeed, we purchase highly processed, nearly unrecognizable food products, molded and packaged in a bewildering variety of shapes, colors, and sizes, retailed through mass corporate industrial supermarkets and fast food chains. We pop trays of “food product” into microwaves because we are so rushed and stressed by our workplaces and schools. Worst of all, we construct elaborate, calorie-obsessed diets that plunge us into sick, mechanical relationships with what we put into our bodies. Food becomes a calculated roster of nutrients, vitamins, minerals, proteins, fats, carbohydrates. Even vegetarian and vegan diets, steeped in narrow moral confines, threaten us with a loss of what is deeply and truly important in the way we eat.

The anarchist community has done a better job than most political groups in placing food close to our hearts, probably thanks to a strong infusion of environmental activists and social ecologists into the anarchist rank and file since the 1960s. Or, perhaps, anarchists just love to eat. At the same time, vegetarianism, veganism, and bioregionalism have made important inroads within the anarchist community, forcing us to confront our individual choices about food and to act with greater degrees of responsibility. In many ways, the intensely personal focus of these varied eating commitments made them especially ripe for absorption into anarchist politics a politics that, like feminism, recognizes that the personal is indeed political.

Yet the limitations of these diet choices have become increasingly evident, and mirror the limitations of anarchist politics more generally. While no one should denigrate people’s “lifestyle” choices, there is a real urgency to move forward with a synthetic political agenda that brings together personal choices with broader activist commitments. Merely being “vegan” is not enough. Not even close. In fact, strict and orthodox moral commitments to a particular diet may actually contravene responsible ecological food choices (using cane sugar as a sweeteners, for example, instead of locally produced honey; eating mass-produced and packaged egg-replacers produced 2000 miles away instead of a free-range egg gathered within shouting distance; refusing to eat a fish caught from a nearby stream while having no qualms about motoring through the Taco Bell “drive-thru” for corporate vegan burritos). Moral orthodoxy, whether in religious or dietary conviction, shuts down more studied and complex understandings of the world around us.

Practical Anarchy is a magazine devoted to heterodoxy rather than orthodoxy. Since this issue of Practical Anarchy is devoted to Food Politics, we will explore a range of critiques and alternatives to the current corporate capitalist food system. Our interest, as always, is to move beyond simplistic debates over “lifestylism,” to reject narrow confines and useless labels like “workerist” or “reformist,” to complicate narrow political choices about what we eat and how we come by it, and to bring a practical dimension to our political choices as an antidote to orthodoxy. We will look both at “negative” activism (activism pitched primarily against some component of the corporate capitalist food regime, which tends to be issue-oriented) and “positive” activism (activism which seeks to build alternative or parallel institutions). We see each of these activist approaches as important and mutually reenforcing.

Most of all, we at Practical Anarchy want to provoke more informed, nuanced, and pragmatic conversations about food and food politics, with the hopes of facilitating stronger activist projects dedicated to food issues. We want roadkill gourmands talking with vegan reichsters. We want environmentalists talking with labor activists. We want libertarian-leaning anarchists talking with social anarchists. Call us naive, say that we are Polyanna-ish, but we believe there is everything to be gained from supporting diverse approaches to food politics and food activism…and everything to lose by ignoring each other and miring ourselves in orthodoxy.

courthouse_t6072.jpg

BURN THEM ALL

In 1855 the Evansville courthouse burned to the ground on Christmas-eve. Why isn’t this a tradition?! In Athens Greece, people torch the giant Christmas tree in front of parliament every year, and then maybe riot. I’d be excited about Christmas, every year, if we could get back to this…

EVANSVILLE: HETEROTOPIA

EVANSVILLE: HETEROTOPIA Notes On Where We Are (and what I’m reading)

When I draw, I scribble.

I place trace paper over the scribble, and connect the lines that I like. The chaos becomes: people lounging, rolling hills, pools of water, houses, gardens, amphitheaters, barns, etc…

Urban planning can be understood much the same way. We can reorganize the lines of chaos. Drawing out what makes sense to us without a template. Using what we have, even if we can’t make sense of the whole, we can make something more meaningful of the few parts that we can grasp. Something about chaos is that it is not without order, but has infinite orders. “In 1900, in poorer districts of Paris, one toilet generally served 70 residents…Le Corbusier, for one, was horrified by such conditions. ‘ All cities have fallen into a state of anarchy,’ he remarked.” ( from The Architecture of Happiness- Alain de Botton) Here, Corbusier uses anarchy interchangeably with chaos. If we define anarchy for ourselves, instead of leaving it to professionals or history, we can redefine the city. We can set new limits. We can draw new lines. These are the lines Corbusier drew, sky scrapers to accommodate 40,000 people, and with lots of toilets.

When I lay trace paper over Corbusier’s drawing, I make something of a different scale. This could be in Corbusier’s Paris, a long walk from the towers, at the top of a hill in the park. A ramshackle silo, a community-hall spanning between tree tops, a collective house in the background with patio, a large pond in the foreground, a mishmash farm house with a black flag hanging from the awning. I could say that this is anarchy in the city, at the scale of companions, of manageable land, in a rift of the woods, with compostable toilets. Using the same materials, Le Corbusier’s lines, I can build what I want.

When we define a thing, be it a city, or anarchy, we set limits to it. We draw it’s edges, length, and size. We decide where it converges, and where it diverges. However, as long as our desire is a determining factor; the whole is dynamic, and the limits are open-ended. In The Owner Builder and the Code the Politics of Buiulding Your Home, co-author ( and self proclaimed “anarcho-decentralist”) Ken Kern remarks on the DIY building experience of psychiatrist Carl Jung: “Significantly, the building was many years in the making, and therefore symbolic of the slow, metered growth of his own consciousness. “ Jung said of his project, ” I built the house in sections always following the concrete needs of the moment…only afterwards did I see how all the parts fitted together and that a meaningful form had resulted…” The section is ended with this “ancient Chinese proverb, Man who finish house, is dead.”

Another author and builder who recognized the importance of impermanence to limits, was architect Cedric Price. Price held a demolitions license and advocated for raze of his constructions on more than one occasion. Believing, as Jung did, to “follow the concrete needs of the moment” might entail bulldozing the concrete that was needed in an earlier moment. Other projects of Price’s worked with open ended limits and impermanent lines. Price developed small structures that could be moved by people, about the city, and installed congruent to the flow of human movement. So, one of these small structures might be set against the entrance to a building, and seem to be the entrance, but when stepped into you might find a hot-tub, a video screen, a table set for tea, etc… and one could step right through on their way, into the building, and so it did act as an entrance. The structure could be set many places, in the middle of sidewalks, wedged between buildings, in empty fields or parking lots, etc… One of his more famous projects was a building with a crane built-in over head, and all the rooms built as self supporting structures, so you could use the crane to move rooms around, stacking them, lining them up, opening up the middle to create a large center room, etc…

Price was determined to build an environment which the purpose of was to be effected by those using it.

The Fun Palace, by Cedric Price, “…dialogue might be the only excuse for architecture.”

A strong point to get down is that we do effect our environments, and they affect us. In Desmond Morris’ book, The Human Zoo, he expands on the civilized trend toward confinement, and the self-destructive behaviors people use to cope. In one section he describes dominating those confined with you, as a way people cope, and says, “It is not enough to have power, one must be observed to have power.” You have to demonstrate your power; your potential to impact your environment must be exhibited. This dynamic might be the crux of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle. Systemic or institutional power often has enormous buildings as obvious monoliths of their power. Colin Ward, in a collection of essays titled, Vandalism, picks up on the smaller signs of power. A broken window can convey that random people have power, and a boarded up window can mean that the people in the monoliths have more control of that power. Morris suggests that this example of Ward’s is significant, in that the board is reactive, and those in control are telling that they are not in total control. It becomes a skill to read the landscape and understand where the seams are tearing, where time has eaten holes, where the cinders will catch, and which strands will fray beyond

the edges. What we might be trying to foster, is a craft, much like cartography. Make a map of where the population is already acting outside the intended use of an area, where crime is congruent to the flow of human movement, where rattling the bars of the cage has shook them loose, where people have exhibited the will and desire to move lines. These points are acutely drawn in URBAN PLANNING AND REVOLT: A SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF THE DECEMBER 2008 UPRISING IN ATHENS, “Urban space operates as a symbol of power and authority, as a signal of overall dominance in political and everyday life… And if the dominant is the person who has the capacity to change the rules (the capacity to install an exception) then the revolted were dominant over the production of their space: they were producers of a rupture in the everyday life of the city.”

In the zine Anarchist Urban Planning & Place Theory, its author, Olympia Teveter, deducts “…that if Geography is the study of ‘place’ and if what they (geographers) study are the unique differentiations at a location and how that location relates to other locations, then geography is in a very rudimentary way the study of environmental differentiations, and a ‘place’ is a perception of unique differentiation in a physical location. That is how you know that you are in a specific place, because you sense its defining, unique characteristics, whether those perceptions are physical or something else.” The unique differentiation in this physical location (Evansville) is our agency, our realizing of the potential to affect our location. Evansville is the space in which our resonance( like string-theory) shapes a geography, where our bodies determine ecology, where our hands leave prints, and our conspiracies take place. We define Evansville. Teveter says, “From my examination of planning and design theory literature at present, almost all of the literature appears to revolve around the nature of ownership…The structure of owner/non-owner is everywhere. “ Most maps of Evansville, use a geography that differentiates what is owned and who owns it, and not who uses it, and how they use it. We want a map of what we can grasp.

In The Future of Vandalism, Colin Ward, quotes N.J. Habraken , drawing the distinction between ownership (or property) and possession, “ We may possess something which is not our property, and conversely something may be our property which we do not possess. Property is a legal term, but the idea of possession is inextricably connected with action. To possess something we have to take possession. Something becomes our possession because it shows traces of our existence…” Habraken goes on to tell what might be done with the “structure of ownership”, “The question is not whether we have to adjust with difficulty to what has been produced with even more difficulty, but whether we make something which from the beginning is totally part of ourselves, for better or worse. The only way in which the population can make its impression on the immense armada which has gotten stranded around our city center is to wear them out. Destruction is the only way left. “ To attempt to take possession of the place we live is to go to war. It has been this way for centuries. The “unique differentiation” of the place of war, is often destruction. The mapping of the state’s offensive is the official destruction, demolitions, neglect, rezoning, highways, commercialism, etc…The mapping of the insurgency is vandalism, necessity, communalism, neglect, the transgression of lines, the breaking of limits, trespassing, etc…

This discussion of difficulty, is brought forward in War and Architecture, by Lebbeus Woods. “The flow of information between people on a communal scale bears a conceptual resemblance to the remnants of war in the old city: it is rational in its intentions, but unpredictable in its effects. …Architecture must learn to transform the violence, even as violence knows how to transform the architecture. …In the spaces voided by destruction, new structures are injected… difficult to occupy, freespaces are, at their inception, useless and meaningless spaces. They become useful and acquire meaning only as they are inhabited by particular people. Traditional links with centralized authority, with deterministic and coercive systems, are disrupted. People assume the benefits and burdens of self-organization…The new spaces of habitation constructed on the existential remnants of war…build upon the shattered form of the old order a new category of order inherent only in present conditions…There is an ethical and moral commitment in such an existence, and therefore a bases for community. “

Lebious Woods’ Scar Construction, “Acceptance of the scar… by articulating differences…divides and joins together… mandates a society founded on differences, not similarities between people and things. The city of self-responsible people… exhibits its unique scars…”

Useless and meaningless spaces; this is what Woods recommends we build. Spaces with no purpose, but to be given purpose by those so inclined to use them. However, Woods understands that this inclination is not one of whimsy, but one of being at war. This giving of purpose is the meeting place of Nihilism and Existentialism. In Ethics of Ambiguity, Simone Beauvoir describes the nihilist as negating meaning, and the existentialist as choosing the void of negation as the space to place meaning. In a way, capitalism makes the project of the nihilist simple. As asserted in Nihilist Communism, capitalism organizes us.

Capitalism reduces, but does not negate, all things to an economic derivative. The capitalist urban planner has, intentionally or not, been busy with the rational project of the reproduction of sameness, a war of leveling. This redundancy allows for the ease of killing all birds with one stone. It has made space for the realization that “All things are possible” Shestove, “All things are permissible” Os Cangaceiros, and “All’s fair in love and war” et al. The project of the nihilist urban dweller is to negate the meaning of spaces, and make them meaningless. Capitalism’s project is similar, is the project of simulation.

“At the dawn of Industrialism, factories were modeled after prisons. In its twilight, prisons are now modeled after factories.” -Os Cangaceiros …

The existential urban dweller doesn’t fill this void, but uses it for the unpredictable,” in spaces within spaces.” Giorgio Agamben says of “an absolutely unrepresentable community”, that it is located in an “unrepresentable space”, which the proper name of is Ease. “The term ‘ease’ in fact designates, according to its etymology, the space adjacent, the empty place where each can move freely, in a semantic constellation where special proximity borders on opportune time and convenience borders on the correct relation.” They say that this use is “the most difficult task”. Here, isn’t a design for utopia. Here we are, in hell.

But, this “coming community”, is existing in-between, in a purgatory, in the possibility of hell or heaven. In Richard Sennett’s book, Uses of Disorder, they write, “… people have learned in their individual lives, the very tools of avoiding pain later to be shared together in a repressive, coherent, community myth…the myth of a common ‘us’ is an act of repression, not simply because it excludes outsiders or deviants from a particular community, but because of what it requires of those who are the elect, the included ones. …this inability to deal with disorder …is inevitable when people shape their common lives so that their only sense of relatedness is the sense in which they feel themselves to be the same. It is because people are uneasy and intolerant with ambiguity and discord in their own lives that they do not know how to deal with painful disorder in a social setting…“ We choose to use the myth of hell, to burn away the memories of a communal history that never happened. The existentialist notes that the design of hell has no exits, only cells for confined security; our project is to “suffer the intrusion of others by necessity.” We cannot blow-up a social relation, but social relations can be explosive. This existential project is to learn how to live in hell, always on fire, making the best of the worst of people. War is difficult, and a way of suffering; the spaces we build must allow for this, as well as freedom. Such a place is Hell.

Hell, with the sinners, criminals, unrepentant, damned, forsaken, and free. Growing up, two of the locations given for Hell were one: the center of the earth, beneath our feet, sloshing back and forth never hitting bottom as the world rotates; and two: in an eternal memory of our lives, reliving every imperfect moment, forever responsible for our mistakes. In both cases, Hell is terrestrial. “In both cases the spectacle is nothing more than an image of happy unification surrounded by desolation and fear at the tranquil center of misery. “ Hell, because in the dichotomy of either or, as well as the in-between either or of the purgatory, we choose hell because we do not choose the bliss of oblivion, the passivity of the object waiting to be acted upon or chosen. We are not the elect, we do not watch for the elected. Hell, because we choose though we are unqualified to choose. Hell, because poverty is miserable, space is alienating, boredom is torment, and survival is hopeless.

Evansville is hell, where we are allowed to do whatever we want, and we will suffer our own affectivity. Ursula K. Le Guinn said of anarchism, “ It is choosing to be responsible for the choices you make.” Our anarchism, our Evansville, is hell; because Heaven is given to us, made for us, purged, purified, and prepared, but we choose hell.

Historic nihilists, in Russia, were educated youth, who chose to live among the peasant villages because there they believed life was closer to its origins, capable of subsistence, and desperate for revolution. When this revolution failed to materialize, they turned to the destruction of the world it was to replace. Today we nihilists might try again. Capitalism has eaten to decay the matter of life for its poor. America has become for many people here, a purgatory, a place of opportunity, a place of potential to reach heaven or be damned to hell. My suggestion is that we choose hell. A heaven here only damns the others to hell. Hell here, displaces heaven and allows for it to be located anywhere. Anywhere Evansville, a home for nihilists, a place built on a space of suspended disbelief. From beneath, behind, about, adjacent, and entangled to a non-local parallel, to “necessities of the particular”…Evansville is empty to such a degree that absence and alienation are the relation most in common. And though for most, a city is defined by the density within geographic limits…we choose a density of interactions, a density of meaning. Hell “exists in a concentrated or diffuse form depending on the necessities of the particular stage of misery which it denies and supports… different forms of the same alienation confront each other, all of them built on real contradictions which are repressed.” We will be unrepressed, unelected, we will unleash the beast and open the gate to hell, not acting out revolution on the stage of misery, but revolting against misery itself we’ll tear apart the stage and decimate the theater of war.

The architecture of this hell is built from a blueprint on the underside of Borges’ map, which hides the natural landscape, and so gives to us a secret world beneath it, ” a unity of misery”. The Art Of Darkness: Deception and Urban Operations depicts this secrecy, in a classic image of hell as a labyrinth. A large city provides several planes of urban high ground, and in many instances a subterranean level in addition … mobility is a great strength. Using back alleys and sewers, slipping through basements…buildings provide cover and concealment; limit or increase fields of observation and fire; and canalize, restrict, or block movement of forces, especially mechanized forces.

Again, Capitalism has already instituted this deception. “Deception is information designed to manipulate the behavior of others by inducing them to accept a false or distorted presentation of their environment- physical, social, or political.”(Whaley) Capitalism’s mode of alienation has displaced people from their environment, both in removing them from a stable location, as well as rendering them incapable of mentally establishing their bearings. People tend to subjectively picture the place they live, eliminating buildings and throughways. This was intentionally used by the KGB in the USSR, where their own maps excluded buildings and areas that the government didn’t want outside forces to be aware of, so upon invasion, enemy forces would be lost in the reality they’d find. (Urban Guerrilla Warfare- Anthony James Joes) This can be used to the advantage of the urban insurrectionist, because the places of “ease”, and the secret passage ways already exist, we already use them to move between the spectacle of the reified world, like dark-matter surrounding the visible universe. We just have to use them now for attack. Miserable, depressed, alone, and tortured, but in solidarity: from hell, solidarity means ATTACK!

TOTAL RESISTANCE : Swiss Army Guide To Guerrilla Warfare And Underground Operations, forwarded by a retired Coronal from the US army. It’s a manual for Swiss citizenry on how to insurrect if occupied by an outside force. In the section General Uprising, it says, “ Procure a lot of city maps for your selves… lease apartments, shops or even houses where you can take up position long beforehand, i.e., at bridges, intersections, train stations, telephone offices, exit routs, etc…

This panel, titled “Security of an Underground Meeting”, makes these suggestions, “reports are made over civilian phones using code words. Pose as newspaper reader-appearance of police vehicles will be reported; pose as a person resting in a park-surveillance of police barracks must be reported; and pose as lovers-approaching of squad car reported…” We don’t need to pose, we are already actually reading, loving, sitting in parks, etc… We have to be vigilant that we’re doing it while at war, that we’re being watched because our regular lives are in conflict with our enemies’ regulations. Life in hell is life at war, and we’ll be damned to hell one way or the other, the point is to choose it. Death comes to us no matter whether we take a position against it or not, but as the bank robber and escapee, Mesrine, said, “No one kills me until I say so.” We can choose to die fighting a war where we take ground, live in a place devastated by our intentions, burn ourselves out hotter than any blue flame of hell’s misery. Life is suffering; I suggest we suffer in love, in passion, and in rage: it will look something like this life looks, because it is this life, because again my point is that we are at war, we have been this whole time, and we will be.

As Colin Ward wrote, “The future will be just like this, only more so.” Let us be more. A density of diffuse commonality, a sudden conclusion of a question, a big bang, a natural phenomenon, normal people uncontrolled, builders of our own architecture we dismantle our own philosophy by constructing our own incomprehensible biology, tear down the fences, get lost in the commons. When we can control our own bodies, it will be far less important for us to control the world around us. But now, we desperately desire private places to do with our bodies what we like. To find those places we must do with the world around us what we like.

PLANNED EXCEPTIONS

Planned Exceptions

In the spaces voided by destruction, new structures are injected. […] They are not predesigned, predetermined, predictable. People assume the benefits and burdens of self organization.

– Lebbeus Woods

Four years ago we bought our house as part of anti-road campaign. At that time, it was common for police to park outside our residence, to tail and stop us, and for the FBI to approach us. We consulted a lawyer, who simply told us: “You are not special. The same things happen to people for being poor and black.” There is nothing exceptional about being targeted and harassed by law enforcement, as there is nothing exceptional about being oppressed in our current social context.

The city authorities threatened to take our house based on building-code violations and quality-of-life regulations. These are not criminal offences—you won’t go to jail. However, you can have your home bulldozed and receive a $10,000 fine. If you have children, the State may take them from you if you can’t provide “appropriate” housing. To deal with this situation, I began to look for information coming from an anti-authoritarian perspective that dealt with housing struggles.

While facing Housing Court, the first folks I decided to read were “anarcho-decentralists” Ken and Barbra Kern. They had written a short history about building regulations, and the extent to which regulations were influenced by material manufacturers’ drive to increase sales. Their work also included a history of people’s resistance to building regulations. The same publication that included the Kern article, also introduced me to an article by Colin Ward.

Ward had come to identify as an anarchist while serving in the British army, and wrote about people’s experiences of housing in warzones. He recalled stories of large segments of London being reconfigured by residents after their homes were bombed by the Nazis, and compared that destruction and displacement to “Thatcher’s bombs.” The term referred to the rampant demolition of houses during the Thatcher administration—a period that included the anti-road campaigns from which we drew inspiration for our highway resistance in the US.

Next, I turned to a publication based out of St. Louis and put together by Mark Bohnert—a local anarchist who had been working with land trusts as a model to secure housing from speculation. This reading led me to meet several people from the city who had been involved in a series of housing squats that were going on six years. Included in Bohnert’s publication was an interview with Joseph Heathcott on cooperative housing projects.

It so happened that Heathcott was born and raised just a neighborhood over from where I live, and so I set up a meeting with him. From our conversations, I learned about the shanty-boat squats on our creek, the history of zoning, and criminalization of our neighborhood. I also learned that Heathcott’s childhood home was demolished for a highway—a story common in the history of the Midwest and post-industrial capitalism.

Following my discussions with Heathcott, I read Murry Bookchin’s Limits to the City and met up with a student from the School for Social Ecology, Matt Hern. I began corresponding with Hern, and he turned my attention to urban living as pedagogy. Hern has published several books on un-schooling, as well as the city. As I read about urban pedagogy, an ongoing theme emerged about the park as an important public space. Considerations of parks lead me to the work of an anarchist professor based in Copenhagen, Nils Norman.

Norman’s writing primarily focuses on the study and exploration of parks. He has drafted plans to design a park for resistance that challenges the dominant logic of urban planners. For example, his design challenges capitalist planners’ design of benches to prevent sleeping, and proposes in their place benches that can be easily transformed into barricades for conflicts with police. Norman draws a great deal from the history of children playing on bombsites, and credits Ward’s Exploding School as inspiration, a concept of learning from the city.

I then read several books by socialist Mike Davis, who, in an Occupied London interview called for collaboration between socialists and anarchists to work on the theme of the city, and argued that the most appropriate vantage point seemed to be insurrection and total destruction. Occupy London later published a book about the insurrection in Greece that included essays on the ways in which the structure of Athens affects resistance, and the large role played by parks and public areas.

Lastly, I read the work of anarchist Abraham Guillen. Guillen writes about urban guerilla warfare, and argues that the insurgent should never try to hold ground or protect a home base. Rather, one should always be on the move—always be on the attack.

In my personal organizing, we have secured our house from codes enforcement (for now), and we learned the unwanted lesson of how to navigate the Housing Court system. However, Guillen is right about the precarity of place, and because of this we have shifted our strategy to purchasing empty lots in our neighborhood in an attempt to inject a common place into the absence we share in common with those around us.

We aim to draw ourselves out of our house and share this emptiness. Somewhere we can stop struggling to maintain shelter for survival, but begin to take exception. Not a place to defend, but somewhere from which to attack. The demolition of our city has opened spaces for open revolt. In spaces without designation we’re left to inject our own imaginations.

Evansville Punk

I have heard about a not too distant past in Evansville, the 80’s and 90’s, when it wouldn’t be uncommon to meet with over a hundred punks. I’ve heard numerous stories about fascist and anti-fascist clashes, general rowdiness, and the politicization of the Evansville music scene, and its disintegration. I would like to solicit stories from folks familiar with that old punk crowd. If you know anything about it, please drop me a line here in the comments section.

Here is an excerpt from an essay written by an Evansville native, Joseph Heathcott, who used to write for Practical Anarchy and Social Anarchism. The full essay is an example of music having an impact on the social positioning and political proclivities of an Evansville that is anti-borders, that is porous and welcomes a flow back in the streets.

The “Man in the Street”

Ska erupted from the working-class shantytowns of Kingston as a vital, dynamic cultural reaction to the control of American popular music by a handful of corporations in the 1950s and 1960s. As Don Drummond’s ska anthem “Man in the Street” suggests, ska constituted a cultural movement that emerged as a soundtrack to the complex daily life of working-class youth in urban Jamaica. Indeed, ska found a ready-made audience in the teeming shantytowns of Jamaican cities. The shantytowns that developed around Kingston and other centers were a product of rural proletarianization, agricultural dislocation, weak formal housing markets, and an underdeveloped public sphere for the provision of basic services. Ska would provide the pleasurable sound against the grind of rapid urbanization, poverty, and rural decline. For the young men and women who had to reassemble dislocated lives and family structures, ska and Jamaican popular culture more generally would provide the resources for creativity and resistance.

The history of the shantytown mirrors Jamaica’s rural and colonial history. The transformation of Jamaica into a modern, capitalist producer economy was effected early on and under conditions of slavery and colonization. Thus, once slavery was abolished in 1834, plantation agriculture competed for labor power with smallholder farming and later with mining operations in the island’s central plateau and the docks of Kingston’s substantial harbor. The result was 150 years of patterned labor migration between plantations, family farms, and mines, as “surplus men” were drained off into work circuits ebbing with harvest seasons. 33

New infusions of British and American capital into Jamaica, first in the 1920s and again in the 1940s, catalyzed forces of rural decline and intensified the proletarianization of Jamaican rural migrant workers. The expansion of capitalist agriculture, coupled with increased mechanization of sowing, harvesting, and processing, disrupted established labor migration patterns. Furthermore, fluctuations in world commodity prices for sugar, bananas, coffee, and bauxite caused further dislocations in the labor force as rural industries laid workers off by the thousands. Throughout the post-World War II period, then, young men and women found themselves increasingly adrift, displaced from plantations through mechanization, from family farms through plantation expansion, and from mines and docks through market depressions. Despite the promise of a Labour government after full independence in 1962, thousands of displaced men and women continued to make their way to the cities each year in search of a livelihood in urban labor markets.

They found livelihoods wanting, however. The few formal economy jobs to be had were in dock work, agricultural and ore processing, and general labor. Highly sought after, these posts in the urban labor market could scant absorb the refugees from a declining rural economy. As a result, most workers in Kingston made a living through the informal economy—black market imports, drug trade, prostitution, numbers, laundry, construction, brewing, hawking, and music performance. Indeed, the shantytown developed as a human catchment, where migrating kin and homeplace networks could readily organize spaces of production and reproduction, as well as strategies of consumption and accumulation. In a nation in transition from colonial subjugation to a postcolonial order, the shantytown underscored the lack of infrastructure, public welfare, and amenities. 36

The shantytowns reflected the spatial logic of colonial capitalist maldevelopment, as well as the remarkable creativity of ordinary people in daily life to carve out livelihoods amid conditions of poverty. It was here that Jamaican working-class people struggled for some amount of spatial autonomy and control over their destinies. In this context, one can not overestimate the importance of music and subculture—especially for urban youth—in forging spaces of resistance and autonomy. It was within this transnational milieu that ska emerged as the principal popular music of Jamaica, and from which it would make its way abroad.

No group in the shantytowns provided ska musicians with a more loyal fan base than the Rude Boys. Rude Boys, stylized by local media as “hooligans” and “gangsters,” were the authors of a working-class youth subculture that arose in the shanties of Jamaica in the early 1960s. Rude Boys (or “Rudies”) were mostly men—but also women in growing numbers—who had been dislocated from rural areas by declining fortunes and opportunities. They flocked to the cities of Jamaica looking for work in export processing, shipping, or petty trading. Most settled in the self-help shantytowns of exploding urban centers such as Kingston, moving between the licit and illicit economy to make ends meet. A vast reserve labor force, working-class urban youth naturally gravitated to the oppositional music of ska and to the Rude culture that supported it.

Rude culture included ways of dressing (high-cuff pants, thin ties, suspenders, and boots), hairstyles (especially the martial flat top), rhythms of speech, in-group slang, alcohol consumption (Red Stripe beer), and attitudes and gestures that defied the authority of parents, teachers, ministers, and police. The Rude life emerged as one of the first great transnational youth cultures. Anchored in a local idiom of resistance, Rudies nevertheless drew on and reinterpreted images of masculinity and liminality purveyed by gangster and western films from Hollywood, spy films from Britain, and kung fu movies from Hong Kong. Ironically, then, while transnational economic processes had displaced youth from the rural areas, the transnational flow of cultural commodities provided the raw material for Jamaican youth to piece together new identities in a fragmented urban world. Moreover, international labor migration networks would soon export Rude culture abroad—particularly to the burgeoning black neighborhoods of Great Britain.

Less and less hopeful that a decent future could be won in Jamaica through formal political action, Rudies engaged in forms of resistance grounded in working-class youth culture and an underground political economy. Rudies supplemented their straight jobs (if they were even able to find work) with illicit activities such as petty theft, drug dealing, gambling, and pimping. Armed with pipe wrenches in the absence of guns, and alienated not only from control over but even from contact with the means of production, Rudies carved up shanties into territories for control over the means of reproduction—particularly loan sharking, prostitution, and building materials provision. Mostly, however, Rudies were engaged in only the pettiest of thuggery. The subculture was principally one of common identification for common survival, with the urban dance hall and the record shop as spatial focal points for mobilizing the resources of identity and resistance to civil authority. Sound masters such as Dodd and Perry often employed Rudies as so-called dance hall crashers, a job that entailed spying on and occasionally provoking trouble at concerts hosted by the competition. Many early ska bands were themselves made up of Rude Boys with instruments. Indeed, as if to compound the Rude mystique, pioneer skaster Don Drummond was arraigned on a murder charge in 1964, and countless other ska musicians found themselves in and out of the slammer on charges ranging from drug possession and racketeering to assault and battery.

By the early-1960s, then, ska and Rude culture pervaded urban areas of Jamaica. A loose core of musicians formed many of the most important bands of the era, with trombonists such as Don Drummond and Rico Rodriguez, saxophonists Roland Alphonso and Hedley, trumpeters Dizzy Moore and Baba Brooks, and of course the great vocals of Stranger Cole, Eric Morris, the Maytals, Derrick Morgan, Jackie Opel, Patsy, Desmond Dekker, the Ethiopians, and the Skatalites. But beyond this core, a transatlantic generation of musicians arrived on the scene to push ska into a variety of directions. Many songs gained transatlantic popularity, such as Freddie Note’s version of the older mento hit “Montego Bay,” the Maytals’ “Monkey Man,” Desmond Dekker’s “It Mek,” Don Drummond’s “Man in the Street,” and Baba Brook’s sexually suggestive “One-Eyed Giant.”

The concerns of ska songs were seldom overtly political in the way those of reggae would be. Indeed, as if plumbing Jamaica’s Protestant Anglican religious history for material, many early ska tunes were retooled gospel numbers or popular ditties with biblical themes. The Maytals released a single with the Vikings in 1963, entitled “The Books of Moses,” and they followed it closely with a rendition of the popular gospel song “Shining Light.” Desmond Dekker reinterpreted another popular gospel number, “Mount Zion,” in the ska idiom, while Clancy Eccles belted a respectable “River Jordan” in cut time.

But ska music also incorporated a number of more secular themes pertinent to urban working-class youth. Ska spoke to the daily frustrations of making a living in the sprawling, inhospitable, and congested city. For example, the Charms’ “Tote Eet” tells of the difficult and demeaning labor that young men must carry out every day in order to feed their families. The Skatalites’ hit tune “Lucky Seven” presents a thrilling, rapid-heart tribute to the dangerous world of urban gambling, where youth often attempt to supplement meager incomes with quick windfalls of cash from numbers and craps. The enigmatic singer Bonny warns every urban youth that “the seed you sow / that’s the seed you reap,” while Clancy Eccles’s heavy-patois “Sammy No Dead” grapples with both homicide and the shantytown rumor mill.

Like the Louisiana R&B tunes that came to the island in the postwar era, ska songs routinely explored issues of love and sex, attempting to make sense of shifting gender roles in the new urban centers. Derrick and Patsy’s “Housewife’s Choice” builds on old blues themes to create a song about the philandering urban flaneur and his conquest of unfaithful wives and girlfriends. The song reverberates with young male fears and tensions about the instability of coupling in the dense urban labor and housing markets of shantytown. These shifting urban contexts create new possibilities of sexual freedom for women and men—and thus new anxieties about gender roles and relationships. These anxieties are also reflected in Stranger Cole’s “Run Joe,” which exhorts the protagonist to flee the scene of an illicit affair with his pants in his hand in order to avoid being killed by a jealous husband. The Silvertones’ “True Confession” pleads with a wronged and heartbroken woman to accept an apology for her mean treatment, while the Dreamletts’ “Really Now” finds a young woman professing her love with uncharacteristic brashness. Jackie Opel’s “Push Wood” and Justin Hines’s “Rub Up Push Up” are also sexually charged, both reflecting heightened levels of contact in urban areas between young men and women outside of the strict purview of parents and a stern rural religious culture. Alternately, Kentrick Patrick’s “Don’t Stay Out Late” entreats young men and women to use common sense, obey parents, and get home from the dance at an early hour.

Ska songs also expressed youth aspirations and fantasies for a more glamorous and carefree lifestyle. Braggadocio was an early and important theme in the genre, as young men attempted to compensate for the alienation and dehumanization of shantytown life and labor. Typical of this variety was Don Drummond’s egocentric “Don Cosmic,” or Roland Alfonso’s hopeful “Streets of Gold.” Just as common, however, were seemingly escapist songs—songs which engaged in fantasy or which reinterpolated popular commercial themes from Britain and the United States. The Skatalites weighed in with such numbers as “Dick Tracy,” while Carlos Malcom and the Afro-Caribs rendered American television’s “Theme from Bonanza” into a rollicking “Bonanza Ska.” Roland Alphonso released “James Bond” in 1965, while numerous ska outfits recorded the fast-tempo “007 Shantytown.” Finally, Baba Brooks paid tribute to the Marx Brothers movies with his 1964 release of “Duck Soup.” Such songs reveal the close affinities ska musicians felt to liminal male characters—tricksters, spies, cowboys, private dicks—as well as the ongoing media and commodity ties between Jamaica, Britain, and the United States.

Movement by ska musicians and Rude Boy fans back and forth between Jamaica and Britain inaugurated a cross-pollination of ska, which increasingly battled with rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, and doo-wop for the hearts of both white and black working-class British youth. Ska—and the engines of commodity production and distribution—put Jamaican musical idioms “out there” into the black Atlantic, to be turned over, reinterpolated, and fragmented into a variety of sounds.

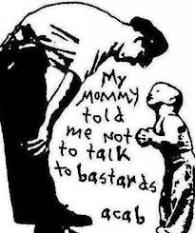

All Evansville Cops Are Bastards

http://www.courierpress.com/news/2013/aug/19/epd-clears-officer/

racial profiling, excessive use of force

In response to the inquiry of the above incident, the Fraternal Order of Police ( the “union” that represents the EPD) asked in the link below “Is it obvious that we’re racist white supremacists? Cause we are!”

http://www.courierpress.com/news/2013/aug/28/evansville-fop-lodge-calls-resignations-robinson-b/

http://www.courierpress.com/news/2010/jul/08/police-party-statements-trial-at-hand-to-begin/

racism, excessive use of force.

The “diversity training” that this lead to was a shameful racist farce. The city’s representative did explain that over 90% of the “local” police force was white, male, and not from Evansville.

Officer convicted of multiple counts of sexual assault on homeless and domestic abuse victim, while on duty.

Officer fired for repeated sexual harassment, while on duty, of Evansville restaurant worker. News reports saturated her description with the fact that she is a bartender, seeming to suggest this somehow made her less credible.

http://www.leagle.com/decision/19921827604NE2d1223_11796

Two officers beat someone they were arguing with, falsely arrest them, and make false reports.

http://www.leagle.com/decision/2000910728NE2d182_1900

Officer sexually harasses teen.

http://www.14news.com/story/22554887/family-says-suspended-epd-officer-inappropriately-touched-boy

Homophobic officer sexually assaults minor in school.

http://www.14news.com/story/7808681/retired-epd-officer-arrested-on-drug-charges

impersonation, resisting arrest and drug possession.

Officer murders lover.

Officer sexually assaults three co-workers. Another officer draws racist cartoons, and still another officer makes false report 911 call to watch porn with room full of cops.

Bazzaro drunk cop waves pistol at restaurant full of people.

http://www.14news.com/Global/story.asp?S=6786991&nav=3w6o

Cop steals from suspects.

http://www.courierpress.com/news/2011/feb/18/resigned-officer-gets-10-fine-suspended-sentence/

Cop beats former cop at cop lodge.

88 complaints against the EPD in two years.

http://indianalawblog.com/archives/2005/08/ind_law_public.html

City signs contract with cop union, agreeing to withhold information of misconducts from public view.

No Justice, Only Fire: Bloomington Anarchists Respond to Homeless Man’s Death

No Justice, Only Fire: Bloomington Anarchists Respond to Homeless Man’s Death

No Justice, Only Fire: Bloomington Anarchists Respond to Homeless Man’s Death

Ian Stark, a 24 year old man experiencing homelessness, froze to death Tuesday night in Bloomington, IN. In response, 50-70 people took the streets on Friday night with torches, banners, spray paint and fireworks to express rage over Ian’s death. The unruly mob, mostly masked up, was comprised of anarchists, anti-prison activists, students, homeless folks, social workers, and others who knew Ian.

“That Crazy Lady Who Shot the Mayor”

The historian Micheal Foucault fanned a discoursive flame into a wild fire when publishing Discipline and Punish, outlining how disciplinarian societies used the panopticon, a design in which the control subject can always be watched but never see when they are being watched, which is supposed to lead to the subject regulating their own behavior out of fear. More current readings of Foucault focus less on the advent of the policing and prison system and more so on sanitation and medical institutionalization as the prime advancement of bio-power, or the advent of control at the perpetual inconstancy of the body. Foucault focused this development on the plagued city, and how the crisis rationalized a totalitarian reordering. Foucault has been criticized for, though being a historian, projecting an ahistorical perspective of bio-power, specifically a misogyny that excludes the history of being female, while denying the specificity of a male history. Silvia Federici, in Caliban and the Witch, points to just this historic period for Foucault’s fumbling, as she chronicles how women were hunted as purveyors of plague and disorder.

Elizabeth Grosz picks up this criticism in an attempt to correct the omission of the actuality of gendered, sexed, and distinctly corporeal bodies. “…women’s corporeal specificity is used to explain and justify the different(read: unequal) social positions and cognitive abilities of the two sexes. By implication, women’s bodies are presumed to be incapable of men’s achievements, being weaker, more prone to (hormonal) irregularities, and unpredictabilities… (that) women are somehow more biological, more corporeal, more natural than men. The coding of femininity with corporeality in effect leaves men free to inhabit what they (falsely) believe is a pure conceptual order while at the same time enabling them to satisfy their (sometimes disavowed) need for corporeal contact through their access to women’s bodies and services. “

According to an “expert” Health witness, Julie Van Orden wasn’t being rational when in 1984 she shot the former Evansville mayor in the face and killed him. She was being irregular. Its thought that Orden was mistaken to think he was even still mayor. Though, it could be that Odren shot Lloyd because he specifically resided over the repeated harassment she endured from the cities governmental functionaries. But what difference would it have made if she had shot the then current mayor instead. Order isn’t inscribed by an individual. Lloyd’s body was subjected to a flow for which he had positioned himself to ebb power’s unpredictability. But power doesn’t flow in merely one direction. The conflict over Orden’s ability to inhabit a space, for sheltering herself, to dwell in a home with her mother; equated its converse when Orden bypassed the mechanistic harvesting of bi-power that Lloyd used in the body-politic, when she realized her corporeal power and showed up by herself at the front door of his house and shot him in the face.

Vetter, The Architecture of Control. “In Jeremy Benthem’s plans for the Panopticon Penitentiary 1791, the design pivoted on the premise that “obedience was the prisoner’s only rational option…Today it goes without saying that any given prison population is calculating, extremely inventive and even incredibly creative, but rarely is it wholly, or even partially, rational. “ Orden’s lawyer argued that she was too mentally ill to understand her actions. So what does it mean if we can’t understand them either.